Colombia's clinical research sector is characterized by a significant paradox: despite possessing numerous advantages that should position it as a leader in Latin America, it consistently underperforms. The country boasts a high-quality, near-universal healthcare system, a large and diverse patient population, and substantially lower trial costs compared to Western hubs. However, Colombia captures a mere 0.2% of the global clinical trials market, with its research activity stagnating over the past decade while regional competitors advance.

This underperformance stems primarily from a systemic inability to attract high-value, scientifically intensive early-phase clinical trials (Phase I and first-in-human studies). This "early-phase deficit" acts as a critical bottleneck, preventing Colombia from leveraging its inherent strengths. The core issues contributing to this are a persistent regulatory labyrinth overseen by the National Food and Drug Surveillance Institute (INVIMA), marked by significant delays and unpredictability, and foundational weaknesses in national infrastructure and investment specifically required for complex early-phase research.

The consequences of this stagnation are severe, including lost foreign direct investment, suppressed job creation, and crucially, restricted access for Colombian patients to innovative, potentially life-saving therapies. This report provides a data-driven analysis of Colombia's competitive gap, investigates the root causes in regulatory and infrastructure deficits, quantifies the economic and human costs, and concludes with a strategic roadmap for bold reforms necessary to transform Colombia's potential into regional leadership and global competitiveness.

Colombia presents a striking paradox to the global life sciences industry. On paper, the nation possesses a formidable array of assets that should position it as a premier, top-tier destination for industry-sponsored clinical research. The country’s healthcare system is internationally recognized for its quality, ranked #22 globally by the World Health Organization, a distinction that sets it apart in the region.1 This high-quality infrastructure is underpinned by a system of near-universal health coverage, providing access to care for approximately 98% of its more than 50 million citizens.2 This vast and accessible patient population is not only large but also genetically diverse and largely treatment-naïve, offering a significant strategic advantage for patient recruitment in a wide range of therapeutic areas.4

Compounding these structural advantages is a compelling economic proposition. The cost of conducting clinical trials in Colombia is estimated to be 30% to 75% lower than in established research hubs like North America or Western Europe, a differential that offers substantial financial efficiencies for sponsors.1 Furthermore, the Colombian government has signaled its intent to foster a knowledge-based economy through R&D tax incentives, including deductions and credits on research-related expenses.4 These factors, consistently highlighted by investment promotion agencies and industry observers, paint a picture of a nation with immense, largely untapped potential to become a leader in the Latin American clinical research landscape.2

Despite this compelling value proposition and a market projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.8% through 2030, the reality on the ground is one of profound and persistent underperformance.10 Colombia’s clinical research sector has failed to translate its potential into a competitive market position. The country captures a mere 0.2% of the global clinical trials market, a figure that underscores its minor role on the world stage.10 More alarmingly, recent data indicates that its research activity has stagnated over the last decade, with the number of new protocols remaining flat while regional competitors advance.11 This report will argue that the core of this strategic failure lies in a critical and systemic inability to attract high-value, scientifically intensive, and financially lucrative early-phase clinical trials, particularly Phase I and first-in-human (FIH) studies.

This early-phase deficit is not merely a symptom of underperformance; it is the central cause. It functions as a strategic bottleneck that prevents the country from capitalizing on its inherent strengths, trapping it in a cycle of dependency on lower-value, late-stage research. This failure has far-reaching and damaging consequences, resulting in lost foreign direct investment, suppressed creation of high-value jobs, and, most critically, restricted access for Colombian patients to the innovative, potentially life-saving therapies that emerge from the forefront of medical science.

This report will provide a comprehensive, data-driven analysis of Colombia’s clinical research paradox. It will begin with a quantitative diagnosis of the country's competitive gap relative to its Latin American peers, establishing the scale of its underperformance. It will then conduct a deep-dive investigation into the root causes of this lag, focusing on the persistent regulatory bottlenecks and systemic unpredictability of the National Food and Drug Surveillance Institute (INVIMA), as well as the foundational cracks in the national infrastructure required for complex early-phase research. Following this diagnosis, the analysis will detail the profound economic and human costs of inaction, quantifying the missed opportunities for economic growth and the direct impact on patient health. Finally, this report will conclude by presenting a strategic, actionable roadmap for policymakers and industry stakeholders, outlining the bold reforms necessary to transform Colombia's paradox of potential into a promise of regional leadership and global competitiveness.

To move beyond anecdotal observations and establish the precise nature of Colombia's underperformance, a rigorous, quantitative analysis is required. This section presents a compelling body of evidence from multiple independent sources to irrefutably demonstrate the country's lagging position within the competitive landscape of Latin American clinical research. The data provides the factual foundation upon which the subsequent analysis of causes and consequences is built, painting a clear and unambiguous picture of a nation failing to keep pace with its regional rivals.

Colombia's role in the global clinical trials market is, by any measure, marginal. The market generated revenues of $162.8 million in 2023, a figure that represents only 0.2% of the total global market for clinical trials.10 While the sector is projected to grow and reach $257.9 million by 2030, this growth starts from a very low base and is insufficient to alter its status as a minor player on the world stage.10

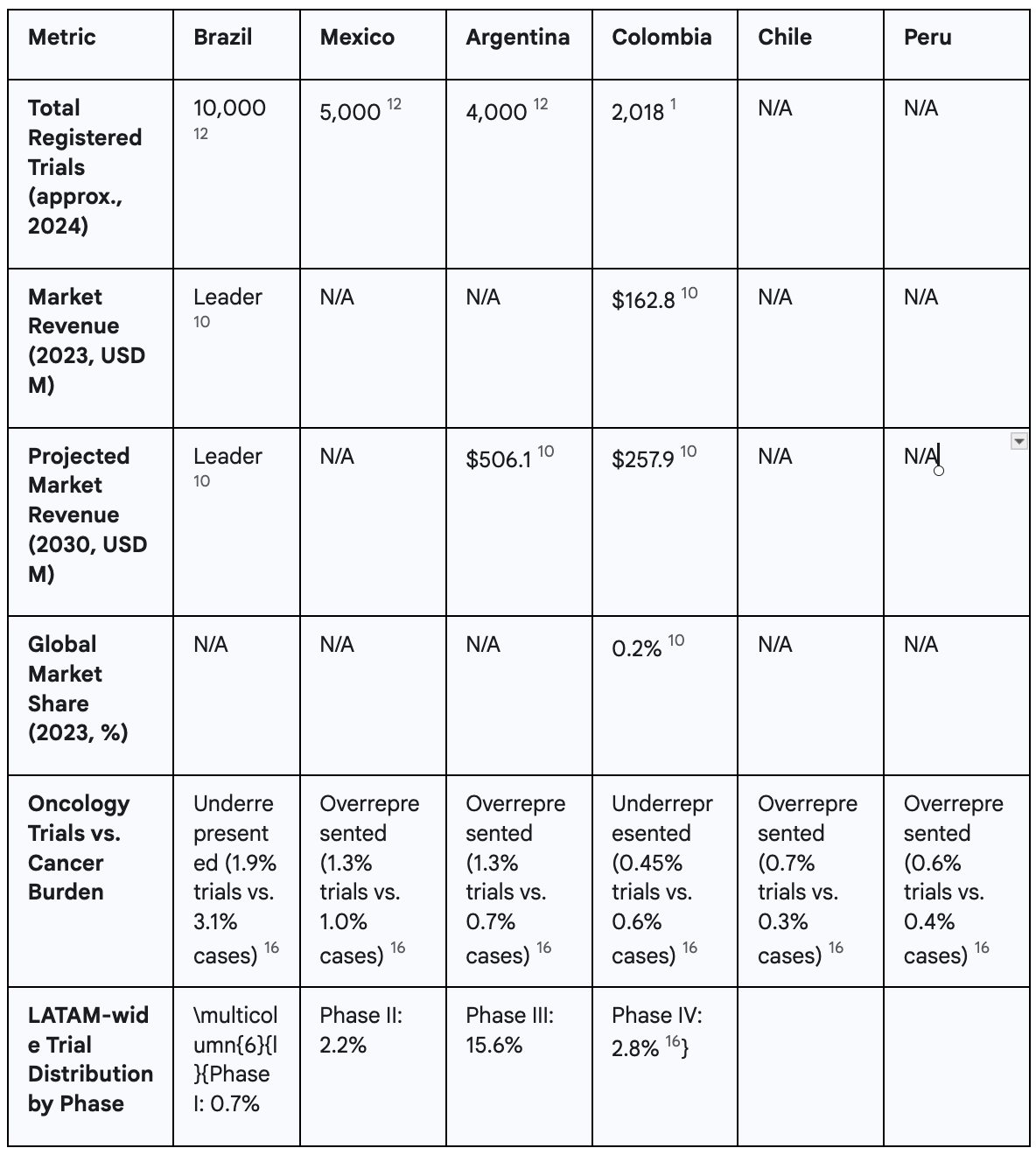

More telling is Colombia's performance when benchmarked against its primary Latin American competitors. The data reveals a clear hierarchy in the region, with Colombia lagging significantly behind the leaders. As of April 2024, Brazil stands as the undisputed regional powerhouse, with approximately 10,000 registered clinical studies. It is followed by Mexico with roughly 5,000 trials and Argentina with 4,000.12 This stark disparity in trial volume illustrates that sponsors are overwhelmingly choosing these other nations for their research activities. This trend is not new; historical data from 2010 to 2018 also placed Colombia behind Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina, as well as Chile, in the number of industry-funded trials conducted.13

Market revenue forecasts further solidify this competitive gap. While Colombia's market is expected to grow, Argentina's is projected to be the fastest-growing in the region, reaching an estimated $506.1 million by 2030—nearly double Colombia's projected revenue for the same year.10 This data directly contradicts any narrative suggesting Colombia is a current leader and instead points to a future where the competitive distance may widen, not shrink.

A specific analysis of oncology trials serves as a powerful case study in this underperformance. The entire Latin American region is already underrepresented in global cancer research, hosting 7.7% of the world's cancer cases but attracting only 3.64% of oncology clinical trials.16 Colombia's situation within this context is particularly dire. The country accounts for 0.6% of all global cancer cases but manages to attract only 0.45% of oncology trials.16 This means that Colombia fails to secure a proportional share of research even within an already underrepresented region. This stands in sharp contrast to its key competitors, Mexico and Argentina, which attract a

higher share of trials relative to their respective cancer burdens (1.3% of trials vs. 1% of cases for Mexico; 1.3% of trials vs. 0.7% of cases for Argentina).16 This crucial difference indicates that Mexico and Argentina are successfully capitalizing on research opportunities that Colombia is demonstrably missing.

Beyond the sheer volume and market value of trials, the type of research being conducted reveals a deeper structural weakness in Colombia's clinical research ecosystem. The nation's trial landscape is heavily and disproportionately skewed towards late-stage research, indicating a significant deficit in the capacity to conduct more complex, scientifically intensive, and financially lucrative early-stage development. In 2023, Phase III trials accounted for a dominant 53.19% of the clinical trial market's revenue in Colombia.10 While a focus on late-phase trials is common in many emerging markets, this extreme over-reliance signals a critical vulnerability and a failure to mature into a more sophisticated research destination.

The crux of Colombia's strategic failure lies in its near-total absence from the early-phase research landscape. A landmark 2024 analysis published by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) delivered a stark verdict: the entire Latin American region has "almost negligible participation" in early-phase research.16 The region as a whole conducts a mere 0.7% of global Phase I trials and only 2.2% of Phase II trials.16 This regional weakness is particularly acute in Colombia. This finding is corroborated by historical data; a comprehensive 2016 report from the Pugatch Consilium, a life sciences policy consultancy, noted that Colombia had only two Phase I trials in operation at that time, a stark contrast to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average of over 90.17 This demonstrates a long-standing and unresolved deficit in the country's ability to attract the foundational studies that drive medical innovation.

This context is essential for correctly interpreting certain market reports. Some analyses have labeled Phase I as the "fastest growing segment" within Colombia's clinical trials market.10 While factually correct in percentage terms, this statement creates a misleading impression of a burgeoning and competitive early-phase ecosystem. The reality is that this high growth rate is a statistical artifact of starting from a near-zero base. An increase from one to three trials, for instance, represents a 200% growth rate, but the absolute number remains globally and regionally insignificant. It does not reflect the development of a robust or competitive infrastructure capable of consistently attracting these complex studies. This "mirage" of progress masks the deep structural weakness that continues to define Colombia's research landscape. The marginal growth observed is wholly insufficient to close the competitive gap with leading research hubs or to establish Colombia as a serious destination for the high-science, high-value work of early-phase drug and device development.

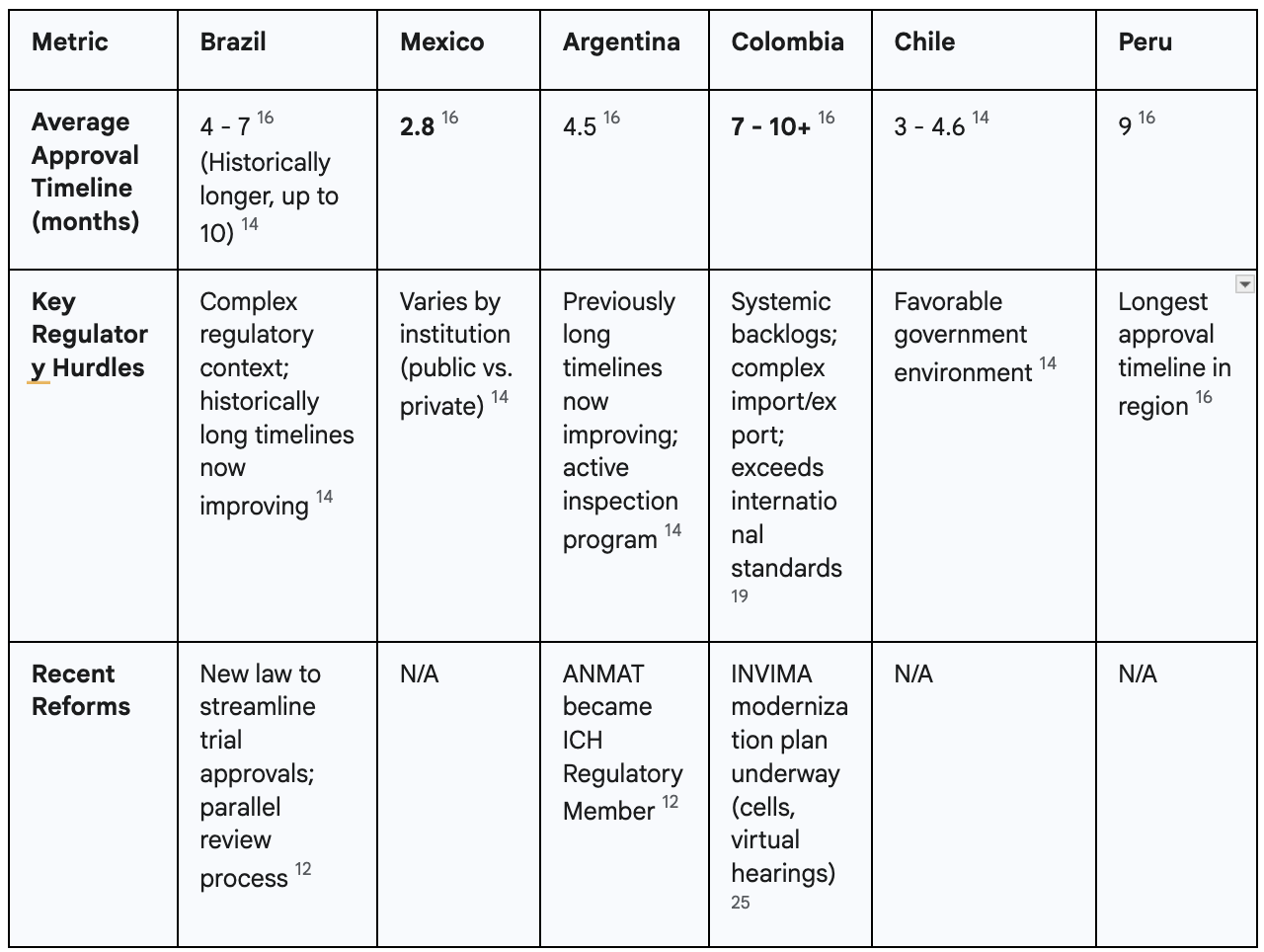

The data clearly establishes Colombia's lagging position in the regional clinical trials landscape. The analysis now turns to the primary cause of this underperformance: a regulatory environment that, despite recent and well-intentioned reform efforts, remains characterized by significant delays, complexity, and unpredictability. This regulatory labyrinth, overseen by the National Food and Drug Surveillance Institute (INVIMA), acts as the single greatest deterrent to international sponsors, particularly those conducting the time-sensitive and high-stakes early-phase trials that are critical for building a competitive research ecosystem.

Regulatory delays are not a new phenomenon in Colombia; they are a deep-seated, historical problem that has long undermined the country's competitiveness. A 2016 report backed by AFIDRO, the association representing research-based pharmaceutical companies, found that the complete approval process for a clinical trial in Colombia took no less than 225 days.17 This lengthy timeline, which included separate reviews by both an ethics committee and the regulatory agency, was identified as among the longest regionally and globally at the time, placing the country at a significant disadvantage.17

Recent evidence demonstrates that this fundamental issue persists. The 2024 ASCO paper on oncology trials reports a current average approval timeline of 7 months (approximately 210 days) for Colombia.16 This duration is substantially longer than that of key regional competitors, most notably Mexico, which boasts an average approval time of just 2.8 months.16 Argentina (4.5 months) and Chile (4.6 months) are also significantly faster, making them far more attractive destinations for sponsors for whom time is a critical factor.16 This data is reinforced by contemporary statements from industry stakeholders. In June 2024, AFIDRO publicly stated that regulatory response times from INVIMA can exceed 10 months, a delay that severely erodes the country's competitiveness and discourages investment.18

The problem of slow timelines is exacerbated by a systemic and growing backlog of applications at INVIMA. Official reports from U.S. government agencies and industry observers confirm that the regulatory body is struggling with a significant accumulation of pending sanitary registrations and other approvals.19 This crisis is attributed to a confluence of factors, including outdated technological infrastructure, limited budgetary and human resources, and the disruptive impact of recent cybersecurity attacks.19 This backlog affects not only clinical trial applications but all pharmaceutical and medical device submissions, creating a climate of uncertainty and delay that ripples across the entire healthcare sector.19

A critical examination of the available information reveals a stark contradiction in the narrative surrounding INVIMA's performance. On one hand, government-affiliated promotional bodies such as InvestInColombia, along with some contract research organizations (CROs), actively publicize a story of dramatic improvement and efficiency. These sources claim that INVIMA has successfully reduced its evaluation times by over 50%, achieving a competitive average of 60 to 90 days for clinical study approval.1 This narrative suggests a modern, responsive, and efficient regulatory agency.

On the other hand, a substantial body of recent, hard data from independent academic sources like ASCO, industry associations like AFIDRO, and official U.S. government reports paints a starkly different picture—one of persistent, lengthy delays and systemic backlogs.16 These two narratives cannot be reconciled as equally true. The most logical conclusion is the existence of a significant gap between the

intent of regulatory reforms and their on-the-ground implementation and impact.

The positive reports often highlight stated goals, pilot programs, or specific successful instances, which may not be representative of the systemic average experience of sponsors. For example, the praise from AFIDRO's director in early 2025 was for a draft reform plan, an expression of hope for the future rather than a confirmation of current, widespread efficiency.20 Conversely, the data on 7-to-10-month timelines reflects the aggregate, real-world experience of companies attempting to navigate the system. This "Reform-Reality Gap" is a critical factor for international sponsors. While the stated intention to modernize is a positive signal, investment decisions are driven by the current reality of risk, delay, and unpredictability. Until the systemic challenges are resolved and the positive results are consistently demonstrable across all applications, the perception of Colombia as a high-friction regulatory environment will persist.

The focus on approval timelines, while critical, can obscure other significant hurdles within the regulatory process that add layers of complexity and cost for sponsors. One of the most frequently cited operational pain points is the cumbersome and often slow process for importing and exporting investigational products, ancillary supplies, and biological samples.21 This process is often separate from the main clinical trial protocol approval and involves navigating customs bureaucracy, which can require additional certifications and permits.22 The guide for handling investigational medicines, published by INVIMA in 2015, was intended to provide clarity on these processes, but challenges remain a significant source of potential delays.24

This is compounded by broader structural flaws in the regulatory framework. The system has been described by industry as "cumbersome and expensive" and characterized by a history of "opaque regulatory practices".17 Furthermore, a report from the U.S. Department of Commerce notes that Colombia sometimes imposes "stringent local requirements that often exceed international standards," including in-country testing requirements for certain imported medicines.19 These additional demands increase the administrative and financial burden on sponsors, making the country less attractive compared to those with more harmonized and streamlined requirements.

In response to these long-standing challenges and persistent industry criticism, INVIMA's current leadership has embarked on an ambitious modernization initiative.25 The new reform plan, often referred to as a "contingency plan," is designed to streamline processes, reduce backlogs, and establish a "procompetitive" regulatory model.25 Key components of this plan include the creation of specialized internal review groups, known as "cells," to triage applications based on risk, and the implementation of virtual hearings to improve communication and transparency between the agency and applicants.25 The agency has also committed to applying these new, more efficient processes to all pending applications, offering a potential path forward for submissions stuck in the pipeline.25

These reforms represent a direct and necessary response to the systemic issues that have plagued the agency. They are a clear acknowledgment of the problems and a credible attempt to address them. However, the ultimate success of this modernization gambit is far from guaranteed. The plan's effectiveness is contingent on INVIMA's ability to overcome the foundational issues that created the crisis in the first place: inadequate budgetary resources, chronic staffing shortages, and outdated technological systems.19 Without sufficient and sustained investment to address these core deficiencies, even the best-designed reforms risk being ineffective. The plan is a promising and essential step in the right direction, but its tangible impact on timelines and predictability remains to be proven. For the international research community, the verdict on INVIMA's transformation is still out.

While the regulatory labyrinth at INVIMA stands as the most immediate and formidable barrier to attracting clinical trials, it is not the only one. Even if the agency's processes were perfectly streamlined overnight, Colombia would still face profound structural deficits that limit its competitiveness, particularly in the critical domain of early-phase research. These foundational cracks—a lack of specialized physical infrastructure and a chronically weak national R&D investment climate—compound the regulatory challenges and trap the country in a cycle of underperformance.

On the surface, Colombia appears to have a robust network of research sites. As of 2024, the country has over 150 clinical research centers certified by INVIMA as compliant with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) standards, as mandated by Resolution 2378 of 2008.18 INVIMA regularly publishes lists of these certified institutions, creating an impression of widespread and sufficient research capacity across the country.29

However, this raw number creates an illusion of capability that masks a critical reality. There is a vast difference between a center being "certified" to conduct a late-phase trial and being "capable" of executing a complex, high-risk Phase I or first-in-human study. The 2016 Pugatch Consilium report was prescient in its warning that only a small fraction of Colombia's certified centers possessed the adequate infrastructure and highly skilled staff required for complex clinical research.17 This gap is particularly wide for FIH trials. These studies demand a level of specialization far beyond what is required for Phase III research, including: dedicated units for intensive pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) monitoring, 24/7 specialized medical supervision, advanced emergency response capabilities, and often residential facilities for healthy volunteers who may need to be observed for extended periods.34 These are high-cost, specialized features that are not standard in most hospitals or even in centers with extensive experience in later-phase trials. While INVIMA provides guidelines for Phase I studies, including the need for complete pre-clinical data, the physical and human capital required to meet these standards is scarce.34

This infrastructure deficit is compounded by a crucial disconnect within the innovation ecosystem. A key finding from industry observers is that the majority of Colombia's research sites lack direct contact with the foreign startup and small biotech companies that are the primary drivers of Phase I development globally.9 These smaller, innovation-focused firms, often backed by venture capital, are the main sponsors of the riskier, more scientifically novel early-stage trials. The fact that Colombian sites are not on their radar indicates a failure not just of physical infrastructure, but of the entire ecosystem to build the networks and reputation necessary to connect with the right international partners.

While the overall landscape is weak, it is not entirely barren. A handful of Colombia's leading academic medical centers and research institutions represent the most viable foundations upon which a true Phase I capability could be built. Institutions such as Fundación Valle del Lili in Cali, Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, Fundación Cardioinfantil in Bogotá, and the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe in Medellín possess the scale, academic rigor, and reputation that could serve as cornerstones for such development.31 Indeed, at least one institution, the Clinical Studies Unit at FCV in Santander, explicitly markets its capacity to conduct studies across all phases, from I to IV, indicating that pockets of ambition and potential capability exist.35

The specific problem of inadequate Phase I infrastructure must be understood within the broader context of Colombia's historically low national investment in science, technology, and innovation.37 Chronic underfunding from both public and private domestic sources has created an environment where there is little to no local capital available to finance the expensive, specialized units required to attract international sponsors. This makes the country almost entirely dependent on foreign investment to build this capacity, yet that same foreign investment is deterred by the very regulatory and infrastructure gaps the investment is needed to fix.

This dynamic creates a self-perpetuating "vicious cycle" of underperformance. The cycle begins with the existing regulatory and infrastructure gaps, which make Colombia an unattractive destination for high-value early-phase trials, causing sponsors to choose more efficient and capable locations. This lack of sponsorship and the absence of robust domestic funding prevent the development of the necessary Phase I units and the cultivation of specialized expertise. The resulting absence of these capabilities makes the country even less competitive, reinforcing its reputation as a location suitable only for late-phase research. This, in turn, leads to missed economic benefits and limited patient access to innovation, which reduces the political and financial capital available for the government to invest in the deep, targeted reforms and strategic investments needed to break the cycle.

The Colombian government has attempted to encourage R&D through a framework of tax incentives, including deductions for R&D investments and tax credits for innovation projects, managed by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (Minciencias).7 While the existence of these incentives is a positive policy signal, their current structure is misaligned with the country's most critical needs in the clinical research sector. The incentives are broad, applying to a wide range of general R&D and innovation activities. A company could, for example, receive a tax benefit for conducting a late-stage trial or for a minor process innovation, neither of which does anything to address the core strategic deficit in early-phase capacity. Because the incentives are not specifically designed to solve the most critical bottleneck, they are largely ineffective at breaking the vicious cycle. To be effective, these financial tools must be strategically retooled to specifically de-risk and reward investment in the areas of greatest need: the construction, certification, and staffing of dedicated Phase I "Centers of Excellence."

The failure to cultivate a competitive clinical research environment, particularly in the early-phase domain, is not an abstract policy issue. It imposes a heavy and multifaceted cost that ripples across Colombia's economy, its healthcare system, and the lives of its citizens. This section details the tangible and severe consequences of this strategic lag, constructing a comprehensive argument that the current stagnation represents a significant and ongoing loss for the nation.

The global clinical trial industry is a powerful channel for high-value foreign direct investment (FDI), bringing capital, technology, and expertise into host countries. While the sector already represents a significant economic activity in Colombia, with the pharmaceutical industry investing an estimated $15 trillion pesos (approximately $3.8 billion USD) annually in research-related activities, its stagnation means the country is forfeiting substantial growth.18 Recent reports have explicitly stated that international laboratories are "losing interest" in conducting studies in Colombia due to the challenging regulatory environment, a sentiment that translates directly into lost investment and missed economic opportunities.11 For sponsors, every day of regulatory delay has a quantifiable operational cost, estimated to be as high as $37,000 USD, compelling them to divert projects and capital to more efficient and predictable locations.44

This lost investment directly suppresses the creation of specialized, well-paying jobs. A thriving clinical research sector is a source of high-value employment for a wide range of professionals, including physicians, principal investigators, research nurses, clinical research coordinators, data managers, and pharmacists.2 The development of this industry has been shown to have a significant social and professional impact, with direct jobs in the sector growing by over 6% annually in past periods of expansion.2 By allowing the sector to stagnate, Colombia is undermining a key pathway to high-quality employment and hindering its national strategic goal of transitioning towards a knowledge-based economy.4

The negative economic impact extends beyond the sector itself, acting as a drag on national productivity. A powerful statistic from the International Monetary Fund (FMI), frequently cited by industry association AFIDRO, demonstrates this link: a 10% increase in local research activity is correlated with a 0.3% increase in a nation's overall productivity.18 This highlights that investment in clinical research is not just a niche industrial policy but a potent catalyst for broad-based economic growth. By failing to foster a competitive research environment, Colombia is actively forfeiting this significant productivity multiplier, particularly during a period of sluggish economic growth.43

The most critical and compelling consequence of Colombia's lagging research environment is the direct human cost. A deficient clinical trial ecosystem, and especially the near-total absence of early-phase trials, denies or significantly delays Colombian patients' access to cutting-edge, innovative therapies that could be life-saving or life-altering.2 For patients with serious or life-threatening conditions for whom standard treatments have failed, participation in a clinical trial can represent the only viable therapeutic option and a source of hope. This is particularly devastating in fields like oncology, where the pace of innovation is rapid and new treatments—such as targeted therapies and immunotherapies—can offer dramatic improvements in outcomes. By failing to attract these trials, the system effectively closes a vital door to the future of medicine for its own citizens.

This lack of access also imposes a significant and quantifiable financial burden on the national healthcare system. A powerful case study from the Centro de Tratamiento e Investigación sobre Cáncer (CTIC), a leading cancer center in Bogotá, illustrates this point vividly.47 Their budget impact analysis found that in sponsored clinical trials, the pharmaceutical or medical device company covers the cost of the investigational product and all associated specialized care, saving the health system significant resources.48 The CTIC study estimated that including just 25% of the center's eligible hematology and oncology patients in sponsored trials could have generated cost savings of over $54 million USD in a single year. Extrapolating this finding, the study concluded that if all potential candidates nationwide were included in cancer clinical trials, Colombia could save approximately 4% of its total national drug expenditure.47

This reveals a "double burden" imposed on the healthcare system by the stagnant research environment. First, the system loses the immediate and substantial cost savings that come from having sponsors cover the high cost of innovative treatments and associated care for trial participants. Second, because patients do not have early access to these innovative therapies through trials, the system is later forced to cover the cost of these same drugs when they eventually reach the market, often at a very high price. This dynamic demonstrates that investing in the attraction of clinical research is not a cost to the public health system, but rather a powerful, long-term savings strategy that improves both financial sustainability and patient outcomes.18

The consequences of the early-phase deficit extend deep into the national scientific and medical community. Without consistent exposure to the complex protocols, advanced methodologies, and cutting-edge science inherent in Phase I and II trials, the skills of Colombian researchers, clinicians, and support staff risk stagnating.9 These early-phase studies are where the scientific frontier is pushed forward, and a lack of participation limits the professional development and global competitiveness of the country's human capital. This can, in turn, lead to a "brain drain," where the nation's most talented and ambitious medical professionals seek opportunities in more dynamic research environments abroad, further depleting the country's capacity for innovation.

Furthermore, a dearth of locally conducted clinical trials creates a significant "local data deficit." The performance, safety, and efficacy of new medicines and medical devices can vary across different populations due to genetic and environmental factors. By failing to conduct a sufficient number of trials within its own borders, Colombia misses the opportunity to generate crucial data on how new interventions perform in the specific context of its genetically diverse population.6 This absence of local evidence hampers the ability of Colombian doctors and health policymakers to make the best-informed, evidence-based decisions for their own people. It also limits the country's ability to contribute meaningfully to the global body of medical knowledge, relegating it from a potential creator of science to a passive consumer.

The preceding analysis has established a clear diagnosis: Colombia's clinical research sector is underperforming due to a combination of persistent regulatory bottlenecks and foundational deficits in infrastructure and investment, particularly for early-phase trials. This final section synthesizes these findings into a set of concrete, multi-layered, and actionable recommendations. This is not a call for incremental adjustments, but for a bold, strategic overhaul designed to transform Colombia from a regional laggard into a competitive leader in clinical research.

The single greatest deterrent to early-phase investment in Colombia is regulatory delay and unpredictability. To address this head-on, the government, through INVIMA, should create a dedicated, parallel, and significantly expedited regulatory pathway exclusively for Phase I and first-in-human (FIH) trials. This "Phase I Fast Track" would not be a minor modification of existing processes but a fundamentally new approach. It should be managed by a specialized, highly trained, and well-resourced review team within INVIMA, with expertise in the unique scientific and ethical considerations of early-phase research. Crucially, this pathway should have a legally mandated, internationally competitive approval timeline of 30-45 days from submission to final decision.

The justification for this radical reform is clear and compelling. It directly targets the primary pain point for the sponsors of innovative, early-stage products, for whom speed to clinic is a paramount concern.16 A fast, predictable, and specialized process would send an unambiguous signal to the global biotech and venture capital communities that Colombia is not just open for business, but is actively competing for high-science projects. This would immediately differentiate the country from regional competitors like Brazil, Peru, and even Argentina, whose timelines remain significantly longer, and position it as the premier Latin American destination for cutting-edge clinical development.

Regulatory reform alone is insufficient if the physical capacity to conduct the trials does not exist. To address the critical infrastructure deficit, the government, led by Minciencias and the Ministry of Health, should launch a national strategic initiative to establish and certify 3-5 dedicated Phase I "Centers of Excellence." This initiative should be structured as a public-private partnership (PPP), co-funded by the government and private industry partners, including pharmaceutical companies, CROs, and private investment funds. These centers should be developed within Colombia's top-tier university hospitals and existing research institutions, such as Fundación Valle del Lili, Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, and others with a proven track record in clinical excellence.31

This targeted approach directly addresses the infrastructure gap identified as a core weakness.9 A PPP model de-risks the high capital investment required to build and equip these specialized units. By concentrating resources in a few elite centers rather than diluting funds across many institutions, the initiative can ensure the development of truly world-class facilities that meet the highest international standards. These centers would become visible hubs of expertise, capable of attracting top-tier sponsors and anchoring a new, more sophisticated research ecosystem.

To catalyze the investment needed for the "Centers of Excellence" and to break the vicious cycle of underinvestment, Colombia must strategically overhaul its R&D tax incentive framework. The current broad incentives, while beneficial, are not targeted enough to solve the specific bottleneck in early-phase research.41 The framework should be supplemented with a powerful, targeted "super-credit" or an enhanced deduction specifically for two activities: 1) capital expenditures related to the construction, equipping, and GCP-certification of dedicated Phase I clinical trial units, and 2) the direct operational costs of conducting Phase I trials within the country.

This reform would align the country's financial incentives with its most pressing strategic goals. It moves beyond the passive encouragement of general R&D to actively and aggressively subsidizing the creation of the exact infrastructure and the execution of the specific activities that the country currently lacks. This targeted financial instrument would provide a clear and compelling business case for both domestic and international investors to fund the development of a Phase I ecosystem, providing the critical missing ingredient needed to break the cycle of stagnation.

World-class infrastructure is ineffective without world-class talent to operate it. The final pillar of a competitive strategy must be a focused effort to cultivate a specialized human capital pipeline. This requires a collaborative initiative between Minciencias, leading universities, INVIMA, and industry associations like AFIDRO to design and implement specialized training and certification programs for the personnel essential to early-phase research.44 This includes clinical pharmacologists, research nurses with experience in intensive monitoring, and clinical trial coordinators with deep expertise in the complex protocols and stringent safety reporting requirements of Phase I studies.

This human capital strategy is essential for ensuring the long-term sustainability and quality of the new Phase I ecosystem. It guarantees that the trials attracted through regulatory reform and new infrastructure will be conducted safely and to the highest international standards, as defined by GCP and Colombian regulations like Resolution 2378 of 2008.29 By investing in its people, Colombia can build a reputation not just for speed and cost-effectiveness, but for scientific and operational excellence, cementing its position as a trusted partner in global drug development.

Colombia stands at a critical juncture. The nation's immense and undeniable potential in clinical research—built on a foundation of a quality healthcare system, a large and diverse population, and significant cost advantages—is being actively squandered. As this report has demonstrated through extensive data and analysis, this failure is not a matter of misfortune but the direct result of a systemic inability to compete in the crucial arena of early-phase clinical trials. This deficit, rooted in persistent regulatory bottlenecks and a pronounced infrastructure gap, has created a paradox where potential remains perpetually out of reach, overshadowed by a reality of regional lag and stagnation.

It is essential to acknowledge that progress is being made. The ambitious modernization efforts underway at INVIMA and the vocal, persistent advocacy of industry groups like AFIDRO are positive and necessary developments.25 They signal a growing recognition of the problem and a willingness to confront it. However, this report must conclude that these incremental changes, while welcome, are insufficient to overcome decades of inertia and fundamentally alter the country's competitive standing in a rapidly evolving global landscape. A bolder, more ambitious, and more strategically targeted approach is required.

The path forward is clear. By decisively implementing a multi-pronged strategy—one that combines radical regulatory reform for early-phase trials, strategic public-private investment in specialized infrastructure, the alignment of financial incentives with this core mission, and a dedicated focus on cultivating human capital—Colombia has the opportunity to break free from its current paradox. It can transform its clinical research sector from a regional laggard into a dynamic engine for economic growth, a vibrant hub for scientific innovation, and, most importantly, a vital conduit for delivering the promise of modern medicine to all Colombians. The choice is not whether to act, but whether to act with the vision and conviction necessary to finally turn a long-held promise into a tangible reality.

1. What is the "Colombian Paradox" in clinical research?

The "Colombian Paradox" refers to the striking contrast between Colombia's high potential for clinical research—due to its quality healthcare system, large and diverse patient population, and lower costs—and its actual underperformance, capturing only 0.2% of the global clinical trials market and experiencing stagnant research activity.

2. Why is Colombia underperforming in clinical research despite its advantages?

Colombia's underperformance is primarily due to a critical inability to attract high-value, early-phase clinical trials (Phase I and first-in-human studies). This is caused by persistent regulatory delays and unpredictability from INVIMA, and a lack of specialized infrastructure and investment needed for complex early-phase research.

3. What are the main issues with INVIMA (National Food and Drug Surveillance Institute)?

INVIMA is characterized by significant delays, complexity, and unpredictability in its approval processes. Average approval timelines in Colombia range from 7 to over 10 months, significantly longer than key regional competitors like Mexico (2.8 months). This is exacerbated by systemic backlogs, outdated technology, limited resources, and cumbersome import/export procedures for trial supplies.

4. What is the "early-phase deficit" and why is it significant?

The "early-phase deficit" refers to Colombia's near-total absence from Phase I and Phase II clinical research. This is significant because these trials are scientifically intensive, financially lucrative, and crucial for driving medical innovation. Their absence prevents Colombia from capitalizing on its strengths, limits patient access to cutting-edge therapies, and traps the country in lower-value, late-stage research.

5. How does Colombia's clinical trial volume compare to other Latin American countries?

Colombia significantly lags behind regional leaders. As of April 2024, Brazil has approximately 10,000 registered clinical studies, followed by Mexico with 5,000 and Argentina with 4,000. Colombia only has around 2,018 registered trials.

6. What are the economic consequences of Colombia's stagnant research environment?

The economic consequences include lost foreign direct investment, suppressed creation of specialized, high-value jobs, and a drag on national productivity. Regulatory delays alone can cost sponsors up to $37,000 USD per day, leading them to divert projects elsewhere.

7. How does the lack of clinical trials affect Colombian patients?

It severely restricts or delays patient access to cutting-edge, innovative therapies, especially for life-threatening conditions where standard treatments have failed. For example, participation in sponsored oncology trials could generate significant cost savings for the national healthcare system by having companies cover the cost of investigational products and associated care.

8. What are the proposed solutions to address Colombia's clinical research challenges?

The report proposes a multi-pronged strategic roadmap:

América Latina podría cuadruplicar su participación en estudios clínicos; en Colombia es clave mejorar regulación - El Tiempo, accessed July 24, 2025, https://www.eltiempo.com/salud/america-latina-podria-cuadruplicar-su-participacion-en-estudios-clinicos-en-colombia-es-clave-mejorar-regulacion-3464636