By Julio Martinez-Clark, CEO, bioaccess®

The United States, a global leader in Medtech innovation, faces a growing challenge: U.S. Medtech startups are increasingly conducting their crucial First-in-Human (FIH) clinical trials abroad. This "innovation paradox" is driven by several factors:

This domestic bottleneck pushes U.S. companies to countries like Australia, Panama, and emerging hubs in Eastern Europe, which offer:

Despite past misconceptions, these international sites adhere to universal quality standards (ICH-GCP), often backed by third-party certifications like IAOCR's GCSA, ensuring data reliability. The offshoring of FIH trials results in economic value leakage, cedes strategic ground to competitor nations, and slows domestic access to breakthrough innovations. To address this, the U.S. needs active policies, including:

Strengthening the entire U.S. innovation chain is vital for maintaining global leadership and ensuring American ingenuity benefits its own economy and citizens.

The United States stands as the undisputed global leader in technological innovation, particularly within the life sciences. The nation’s innovation ecosystem, a powerful confluence of world-class universities, abundant venture capital, and a culture of entrepreneurship, is unparalleled in its ability to generate groundbreaking ideas. A cornerstone of this success is the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, a landmark piece of legislation that unlocked the commercial potential of federally funded research conducted in academic laboratories.1 By allowing universities to retain intellectual property rights, the Act catalyzed a torrent of technology transfer that has fueled American economic growth and competitiveness for over four decades.3

The results of this policy have been staggering. Between 1996 and 2020 alone, technology transfer from American universities resulted in over 554,000 disclosed inventions, the granting of 141,000 U.S. patents, and the formation of more than 18,000 startup companies. This activity contributed an estimated $1.9 trillion to the U.S. gross industrial output and supported millions of jobs.2 Every day, on average, three new startups are formed and two new products are launched based on university inventions, a testament to a system that excels at the front end of the innovation lifecycle: discovery and company formation.2

Yet, beneath this story of success lies a critical paradox. While the U.S. excels at creating medical technology intellectual property, it increasingly struggles to shepherd its most promising innovations through their first, and arguably most crucial, clinical validation stage. A growing number of high-potential Medtech startups, often spun out of elite institutions like Harvard University and innovation hubs in Boston, San Francisco, and Minneapolis, are compelled to leave the country for their first-in-human (FIH) trials.4 These trials, particularly for high-risk, implantable Class III (PMA) devices, are the essential stepping stone where a laboratory concept is first tested in human subjects. This is the moment an invention must prove its fundamental safety and potential efficacy, transforming it from a promising idea into a viable therapeutic candidate.4

This exodus is not a matter of mere business convenience; it points to a significant vulnerability in the national innovation strategy. The very system that was designed to ensure the economic benefits of U.S.-funded research accrue to the American economy is witnessing a critical stage of value creation move offshore. When a startup successfully completes an FIH trial, its valuation can increase dramatically, marking a key "value inflection point" that attracts acquisition by global Medtech giants.4 The fact that this pivotal event frequently occurs on foreign soil, utilizing foreign infrastructure and benefiting foreign economies, represents a significant leakage in the U.S. innovation value chain. Systemic financial, regulatory, and bureaucratic hurdles within the United States are creating a validation bottleneck that forces American ingenuity abroad, risking the long-term erosion of economic value and ceding strategic ground in the global life sciences race.

The decision for a U.S. Medtech startup to conduct its first-in-human trial overseas is rarely a choice of first preference. It is a decision compelled by a set of formidable domestic hurdles that are not incidental but are deeply embedded features of the American healthcare and regulatory landscape. These challenges are so profoundly integrated into the U.S. system that they appear almost insurmountable for capital-constrained startups operating on aggressive timelines.4 The problem is systemic, creating a powerful "push" effect that sends American innovation to foreign shores.4

The most immediate barrier is the sheer cost of conducting clinical procedures in the United States. For a startup company paying for trial-related expenses out of pocket, the price of hospital services, imaging, and specialist consultations can be prohibitive.4 This financial pressure is magnified by the intense cash "burn rate" characteristic of these ventures. With highly paid professionals on staff, rent for facilities, and other operational expenses, a Medtech startup can easily burn through $30,000 or more per day. Under the constant watch of investors who expect a timely return on their capital, every delay and every unforeseen cost escalates the risk of failure.4 The high-cost U.S. environment creates a financially punishing landscape for the lean, fast-moving startups that are the lifeblood of the innovation economy.

Beyond cost, startups face significant challenges in recruiting clinical investigators and partner hospitals within the U.S. Leading physicians and academic medical centers are often hesitant to take on high-risk FIH trials for several reasons. First, these trials are subject to intense scrutiny from institutional review boards (IRBs), the FDA, and the public. A single adverse event, even one that is not unexpected in a pioneering trial, can generate negative publicity and pose a significant liability risk for both the investigator and their institution.4

This inherent risk is compounded by staggering levels of bureaucracy. The U.S. healthcare system is dominated by massive hospital networks, each with its own complex administrative structure. As an example, securing a partnership with a major institution like the Mayo Clinic can require navigating a labyrinth of committees and administrative approvals just to arrange an initial meeting with a potential investigator.4 For a startup that measures progress in days and weeks, these months-long bureaucratic delays are untenable.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), tasked with ensuring patient safety, naturally maintains a highly cautious and risk-averse posture, particularly concerning FIH trials of novel, high-risk devices.4 While this mission is laudable, its practical application creates substantial "red tape" for innovators. The agency often requires extensive, time-consuming, and expensive preclinical validation, including numerous animal studies conducted in specific ways at designated labs, all designed to de-risk the transition to human subjects.4 For a large, established corporation, these requirements are manageable. For a startup, they represent a significant extension of the pre-revenue development timeline, further depleting limited capital reserves and delaying the crucial validation milestone.

These hurdles do not exist in isolation; they create a self-reinforcing cycle of risk aversion. The high costs and legal exposure make hospitals and investigators wary of participating in FIH trials. This institutional reluctance, in turn, reinforces the FDA's cautious approach, leading the agency to demand even more comprehensive preclinical data to mitigate potential risks. This demand for more data further inflates the cost and timeline for the startup, making the trial an even less attractive proposition for the already hesitant clinical partners. The result is a vicious cycle that systematically filters out many small, innovative firms, effectively pushing them to seek environments where this cycle is broken and innovation can proceed at a more viable pace.

To understand the powerful "pull" of international trial locations, one must first understand the fundamental business model of a venture-backed Medtech startup. These companies are not built for long-term, incremental growth; they are designed for speed. Investors, having placed significant capital into a high-risk venture, typically expect a substantial return—often in the range of 10 times their initial investment—within a compressed timeframe of five to seven years.4 This model makes time the single most valuable, and most perishable, currency.

The entire lifecycle of a startup is oriented around reaching key milestones that unlock the next tranche of funding or, ultimately, an acquisition by a major industry player like Medtronic or Boston Scientific. In the world of Medtech, the most critical of these milestones is the successful completion of the first-in-human trial.4 This is the "value inflection point" where a technology's safety and efficacy are demonstrated in humans for the first time. The moment a company can present positive FIH data, its valuation can "skyrocket," transforming its negotiating position with potential acquirers and validating the investors' bet.4

It is this relentless pressure to reach the value inflection point as quickly as possible that drives U.S. startups overseas. While conducting trials abroad can be less expensive, the primary motivation is not direct cost savings. The true prize is time savings.4 Every day saved on regulatory approval or patient recruitment is a day less of cash burn, bringing the company one day closer to its critical milestone. The financial savings are an indirect but significant consequence of this radical time compression.

A competitive global market has emerged to meet this demand, with several nations and regions developing ecosystems specifically designed to accelerate clinical trials.

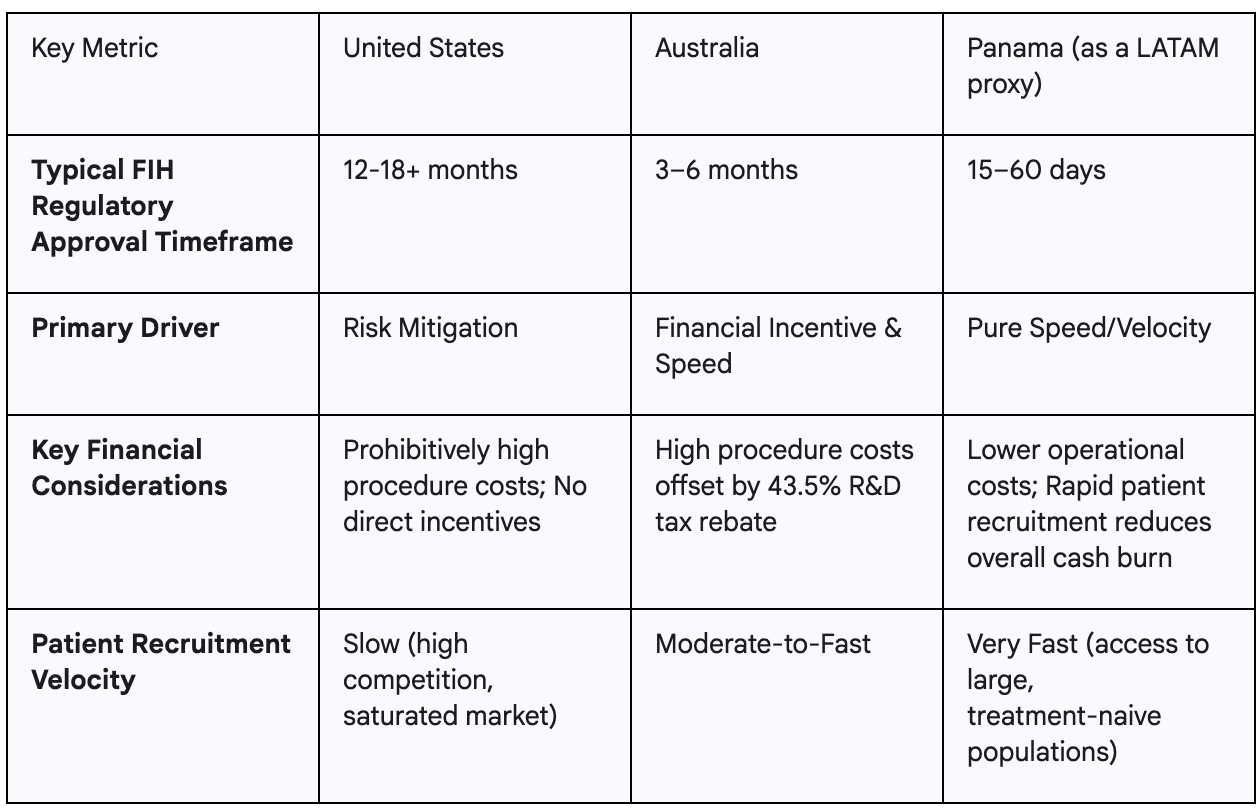

This global competition is not a random occurrence. It reflects the emergence of a de facto international industrial policy for clinical trials. Nations are actively competing to attract this high-value R&D activity. Australia’s tax rebate is a deliberate, targeted industrial policy designed to build its life sciences sector. Panama’s ultra-fast approvals function as a non-financial industrial policy, creating a powerful competitive advantage based on regulatory efficiency. The United States, by contrast, has no such strategy. Its slow, expensive, and bureaucratic system functions as a de facto policy of discouragement, inadvertently fueling the growth of life science innovation hubs in competitor nations. The stark differences in these environments present a clear business case for startups, as illustrated below.

A persistent and understandable concern surrounding the trend of offshoring FIH trials is the question of data quality. A common misconception holds that research conducted in emerging economies, sometimes pejoratively labeled "third world countries," is inherently less rigorous and that the resulting data may not be reliable.4 While this may have been a valid concern in decades past, it reflects an outdated view of today's globalized clinical research landscape. The reality is that a new geography of clinical excellence has emerged, built on a foundation of universal standards, independent certification, and powerful market forces.

The first pillar of this new paradigm is the near-universal adherence to global standards. Credible clinical research sites around the world, regardless of their location, rigorously adhere to the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) established by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH).4 ICH-GCP is the international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting trials that involve human subjects. Compliance is not optional for sites wishing to work with U.S. or European sponsors, as the data generated must ultimately be acceptable to regulatory bodies like the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

The second pillar is the rise of independent, third-party quality certification, which provides an objective measure of a site's operational excellence. A key player in this space is the UK-based International Accrediting Organization for Clinical Research (IAOCR), which offers a Global Clinical Site Assessment (GCSA) certification.4 The GCSA is not a simple checklist; it is a comprehensive, 7-module assessment of a site's core processes, including governance, business strategy, patient engagement, and workforce quality.6 The credibility of this certification is rooted in its development; it was created in consultation with industry leaders like IQVIA, PPD, and Parexel, as well as government bodies such as the UK's National Health Service (NHS), and its standards are aligned with UNESCO's International Standard Classification of Education framework.4 Crucially, sites in the very regions attracting U.S. startups—including Colombia, Mexico, and Panama—are now actively pursuing and achieving GCSA certification, making a tangible and verifiable commitment to meeting world-class quality standards.4

The third and perhaps most powerful pillar of evidence is the behavior of market leaders. In late 2024, Velocity Clinical Research, the world's largest fully integrated network of clinical trial sites, announced its strategic expansion into Latin America.4 The company, which already has a massive footprint in the U.S. and Europe, identified Latin America as the "natural next step" for its global growth, targeting major markets like Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico.9 A sophisticated, data-driven market leader like Velocity would not make such a significant strategic investment unless it was confident in the quality of the region's clinical infrastructure, the talent pool of its investigators, and the long-term viability of the market. This move serves as a powerful, third-party market validation of the region's rising quality and maturity.

These developments reveal that quality in the global clinical trial landscape is no longer just a top-down regulatory mandate; it has become a market-driven commodity. In order to compete for lucrative contracts from U.S. and European sponsors, international sites must differentiate themselves on the basis of quality and reliability. A site in Panama that can present a GCSA certificate to a potential startup partner from Boston has a significant competitive advantage over a non-certified competitor, as it signals lower risk and higher data integrity. This creates a powerful market incentive for all sites in a region to invest in quality and pursue certification to remain competitive. The entry of major players like Velocity further professionalizes the market, raising the bar for all participants. The rising quality in these emerging hubs is not a coincidence; it is the predictable and positive outcome of intense global competition for high-value Medtech and biopharma business.

A critical and often misunderstood element of this global dynamic is the rapid pace of patient recruitment in emerging markets. This speed is a key component of the time savings that U.S. startups seek, but it raises an important ethical question: Why are patients in these regions so willing to participate in high-risk, first-in-human trials?.4 A superficial analysis might suggest a potential for exploitation, but a deeper look into the local context reveals a more nuanced and symbiotic relationship.

The answer lies in the structure and performance of the public healthcare systems in many of these nations. These systems are typically run by the government and, while often providing a basic safety net, can be inefficient, underfunded, and difficult for ordinary citizens to navigate.4 For the "regular Joe on the streets," gaining access to specialist care, advanced diagnostics, or expensive procedures can involve long, frustrating delays. It is common for patients to be placed on waiting lists for months or even years to see a specialist or receive a critical surgery.4

In this context, a clinical trial is often perceived not as a risky experiment, but as a gateway to otherwise inaccessible, high-quality medical care. For many patients, it represents their only "way in" to a system that can provide the treatment they desperately need.4 The benefits of participation are tangible, immediate, and often delivered with a level of dignity and support that the public system cannot offer. These benefits include:

Therefore, the decision to participate is often a highly pragmatic one. This creates a powerful symbiotic relationship: the U.S. startup, blocked by hurdles at home, gains access to the patients and data it needs to advance its technology and create value. In return, the patient gains access to advanced medical care that could save or dramatically improve their life. This dynamic is a compelling example of global markets creating a solution that addresses two distinct systemic failures simultaneously. The U.S. system fails at providing efficient clinical validation for its own innovators. Concurrently, the public health systems in many emerging markets fail at providing timely, quality care to all their citizens. The global clinical trial industry has emerged in the gap between these two problems, creating a transactional relationship that provides a powerful, if partial, solution to both.

The offshoring of first-in-human trials is more than a business trend; it is a flashing indicator of a critical vulnerability in the U.S. innovation lifecycle. The nation has masterfully crafted policies like the Bayh-Dole Act to foster the "front end" of innovation—the generation of world-class research and the formation of startups.2 However, it has neglected the "back end," creating a domestic clinical validation environment that is uncompetitive, slow, and prohibitively expensive for the very innovators it aims to support.4 This imbalance forces American ingenuity to seek validation abroad, with significant consequences for U.S. economic and strategic interests.

The cost of inaction is steep. First, the U.S. risks a substantial loss of economic value. When the pivotal FIH trial—the key "value inflection point"—occurs in Panama or Australia, a significant portion of the value created is realized offshore, benefiting foreign economies and clinical ecosystems.4 Second, the U.S. is ceding strategic ground in the global life sciences race. By exporting these high-value R&D activities, the U.S. is actively funding the development of clinical trial infrastructure, regulatory expertise, and skilled human capital in other nations, effectively building up the capacity of its future competitors.4 Finally, and most importantly for American citizens, this dynamic can slow domestic access to innovation, forcing U.S. patients to wait longer for breakthrough technologies that are being tested, validated, and proven effective elsewhere first.

Addressing this challenge requires the application of "tech realism"—a core principle of ITIF that recognizes the need for smart, active policies to support innovation in the face of global competition.12 The U.S. can no longer afford a purely hands-off, market-absent approach when other nations are implementing deliberate industrial policies, like Australia's 43.5% R&D tax rebate, to attract these critical activities.4 The goal should not be to halt global trials, which play a vital role in medical advancement, but to make the United States a more competitive and viable option for its own domestic startups. The assertion that the U.S. system is "impossible to fix" in the short term should be taken not as a statement of fact, but as a direct challenge to policymakers to prove otherwise.4

To restore competitiveness and strengthen the entire U.S. innovation chain, policymakers should consider a multi-pronged strategy:

Ultimately, America's global leadership in the 21st century will depend on its ability to nurture every link in the innovation chain—from the initial spark of an idea in a university lab to the final delivery of a life-saving product to a patient's bedside. A failure to address the clinical validation bottleneck is a failure to fully capitalize on the nation's greatest economic strength: its boundless ingenuity. The time to act is now, before more of that ingenuity is forced to prove its worth on foreign soil.

The "innovation paradox" of U.S. Medtech, where world-class research and development are increasingly validated abroad, signals a critical weakness in the nation's innovation ecosystem. While the Bayh-Dole Act has been instrumental in fostering discovery and company formation, the domestic environment for First-in-Human (FIH) trials has become uncompetitive due to prohibitive costs, bureaucratic inertia, and a risk-averse regulatory posture. This forces American ingenuity overseas, leading to economic value leakage, the ceding of strategic ground to competitor nations, and delayed access to cutting-edge medical technologies for U.S. patients.

The global landscape has evolved, with countries like Australia, Panama, and emerging hubs in Eastern Europe actively competing for high-value R&D by offering accelerated approvals, financial incentives, and rapid patient recruitment without compromising on quality standards. This global competition, driven by deliberate industrial policies, highlights the urgent need for the U.S. to adopt "tech realism" and implement active strategies rather than a hands-off approach.

To maintain its global leadership in Medtech, the U.S. must address this bottleneck by:

By strengthening every link in its innovation chain, the U.S. can ensure that American ingenuity benefits its own economy and citizens, securing its position at the forefront of global medical advancement.